Más Información

En SLP nunca ha existido una gobernadora y ahora hay una posibilidad real que así sea, asegura Ricardo Gallardo tras aprobación de "Ley Esposa"

Morena analiza disminución de pluris y elección popular de consejeros del INE: Monreal; serán revisadas en la reforma electoral, dice

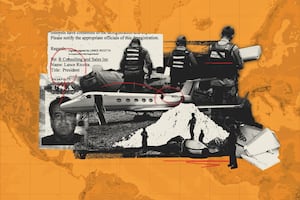

Rastro de jets vinculados al narcotráfico lleva a un vendedor en California… y a un punto ciego de la regulación aérea en Estados Unidos

Secretaría Anticorrupción sanciona a dos empresas por buscar contratos con información falsa; imponen multa de miles de pesos

Banxico se despide de 2025 con otro recorte a la tasa de interés; queda en 7% por ajuste de 25 puntos base

Last week immigrants, their families, and legal advocates rallied outside the U.S. Supreme Court as eight justices heard oral arguments in United States v. Texas, an immigration case concerning the Obama Administration’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) program, which would have offered deferred action status and work authorization to nearly 4 million unauthorized immigrants.

Based on the photos and news coverage of the demonstrators, the working parents, restaurant owners, and other small business and household employers who break U.S. immigration laws by hiring unauthorized immigrants were, as usual, noticeably absent.

Too often immigration is seen as a problem for immigrants and their families. But if you hire someone to care for a family member at home, buy produce at the grocery store, eat out at a restaurant, or have your house cleaned, the fight to legalize the status of unauthorized workers is your fight, too.

According to the most recent data gathered in 2012, 8.1 million of the estimated 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants were employed. They represented 5.1 percent of the United States workforce. Some of the industries with the highest numbers of unauthorized immigrant workersinclude landscaping services, private households, crop production, dry cleaning services, construction, and eating and drinking establishments. Thus, many Americans benefit from the work of unauthorized immigrants either because they employ these immigrants illegally or because the goods and services they consume are made cheaper by the use of unauthorized immigrant labor.

Unauthorized immigration and the hiring of unauthorized immigrants is a kind of workaround against immigration laws that do not reflect labor demands. As Americans have become olderand more educated, the demand for lower-skilled workers, namely workers in occupations that do not require a high school diploma, has been met by immigrants. Yet lower-skilled workers only qualify for a handful of visas that would allow them to work lawfully in the United States, in part because U.S. immigration laws favor family immigration and higher-skilled temporary workers.

The lack of sufficient channels of lawful entry for lower-skilled workers makes it difficult for them to stand in line and wait their turn for legal entry and difficult for employers who need lower-skilled workers to find workers authorized to work, which results in rule breaking by both parties.

If so many people are breaking the law — both immigrants and United States natives — it begs the question: are bad laws happening to good people? Yes, and everyone implicated by these laws should be fighting to fix them.

Household employers, small business owners, and consumers should push to legalize the status of those workers already in the United States, advocating for the creation of new visa categories for lower-skilled work, as well as easier ways for employers to verify that employees are authorized to work.

Opponents of legalization and visas for lower-skilled workers often argue that such measures would cause U.S. workers to be displaced. But this is not true. First, arguments about displacement are a red herring in the debate about whether to provide a path to legal status for the more than 11 million unauthorized immigrants already in the United States, since more than 8 million of them already have jobs in the United States.

Second, most economists agree that immigrants and native U.S. workers do not generallycompete for the same work and when they compete, they have different skills, language and education, which positions each group differently in the job market. When immigrants enter the workforce they often cause U.S. workers to specialize or they engage in work that complements the work of U.S. workers. In the restaurant industry, for example, native-born workers move to communication-intensive work in the front of the house and immigrants focus on manual labor in the back of the house.

Any residual concerns about displacement could be addressed by tying any new immigration to employment and labor conditions in the United States.

Fixing immigration laws to provide legal status to individuals already working in the United States could also result in higher wages and more rights for people who are currently unauthorized to work. And yes, even those who support immigration might worry that higher wages could make it more expensive to go out to eat or tackle projects like remodeling a kitchen.

But not fixing our laws because of wage concerns would mean a tacit endorsement of black market wages and the hiring of cheap immigrant labor over more expensive U.S. workers.

Finally, a focus solely on enforcement, which some candidates have called for, will not effectively disrupt the demand for immigrant labor or deter rule breaking. We simply do not have the financial resources or personnel — nor does it make sense — to deport 11.3 million people, build a wall across a nearly 2,000-mile border with Mexico, or go after restaurant owners, working parents, cooks, nannies or roofers.

This is not an indictment of people who hire unauthorized workers. Instead, it is a call to action. It’s time to broaden the coalition and demand that politicians offer solutions that fix our immigration laws so good people — immigrants and citizens alike — do not feel compelled to break them.

Noticias según tus intereses

[Publicidad]

[Publicidad]